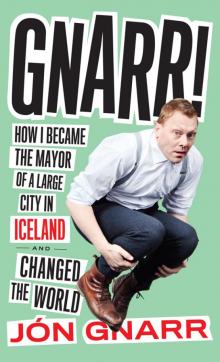

Gnarr Read online

Page 2

The most famous Icelander is Björk. Despite everything, she’s always remained herself. Abroad, she constantly has to flee from fans and journalists who pursue her into every little corner, while in Iceland you run into her in the pool, on the bus, or in the shops. In general, she’s left alone.

In Iceland I was famous by the time I was fourteen. I was a fourteen-year-old with a Mohawk and a ring through his nose, and this too was news. By the time I was thirty, and earned my living as a comedian and actor, almost every child in Iceland knew me. Whenever I was appearing in some television series, the city was filled with huge advertising posters with a picture of me on the walls of the houses. And when I got onto a bus, it was quite likely that the bus would be running ads for me too.

It was quite a sensation if somewhere or other some elderly guy didn’t know who I was. Once, somebody told me about one such old timer who in all seriousness had never heard of me—this aroused laughter from those standing around. As you can see, being famous is different in Iceland from what it is elsewhere. In Iceland, everything is boringly normal. Even celebrity. People know that before you go swimming, you stand there naked in the shower just like they do.

The only practical use of celebrity is that it sometimes saves you having to queue for the clubs on the weekends. But at clubs, like everywhere else, you’ll most likely have to join the line like all the other well-behaved folk. Even Björk joins the line at the end and waits until it’s her turn, and everyone finds this normal. Sometimes a bouncer decides to show her preferential treatment, but the bystanders find this misplaced and awkward.

The Icelandic state of mind is dominated by the seasons. Summer is the best time. On the “first day of summer” (which according to the calendar is the third Thursday in April), we all wish each other “Have a great summer!” This is a nice custom. In summer, everyone is happy. There’s hardly an Icelandic poet who hasn’t, sooner or later, sung about our summer, our wonderful summer, which is so much better than any other summer in the world. Although not all that much better, actually.

We have to use the power of positive thinking, to enjoy the half-full glass. The thermometer rarely manages more than 20 degrees Celsius (68°F), but the minute it hits ten degrees (50°F), we pull all our clothes off. Temperatures much above this are considered a heat wave. In summertime, the living is easy. And when someone indulges in pessimism, we just turn a deaf ear. Everyone’s optimistic and cheerful, we’re the happiest people under the sun—because it’s summer.

With the fall, comes fear. The days get shorter and the nights, as a result, longer. Suddenly our worries are back. We wonder whether it’s going to be a hard winter.

When winter comes, we stick our heads under the duvet. Now is the time to stay at home. There’s not much energy left for winter romances in this country. Not only do we not have any real summer, but no real winter either. If it snows one day, there’s a frost the next day and on the third day it rains. The lakes are frozen in the morning and thawed again in the evening. You never know what to expect. That’s why, unlike the other Scandinavians, we Icelanders have never made much headway in the winter sports. The only sport we’re really good at is chess. After all, indoors you can hunker down at the chessboard all year round.

We are shaped through and through by nature and the elements. We have a tremendous ability to adapt—and you need plenty of that if you want to survive in this country. You can never rely on everything staying the way it was here. The earth might quake or a volcano could erupt. Your garden might get buried under a lava flow, and there are snow storms in June. But we’ve learned to live with it—perhaps because we’ve maintained a certain degree of humility towards nature and her moods.

Nature we cannot change, but we can change ourselves and our way of thinking. To nature we can only adapt. We go fishing when the sun shines and we make hay when the sun shines. This adaptability has always been our strength, as it’s the only way to survive here. If you don’t make an effort, don’t store provisions, and don’t use the opportunities that present themselves to you, then when winter comes you’ll simply starve.

SEND IN THE CLOWN

I was born into a working-class family in Iceland. We lived in a Reykjavík suburb on a street called Kurland, named after a Norwegian village. My parents were ordinary folk. My mother worked in a hospital canteen and my father was a policeman, but he never got very far in his career because of his Communist views.

By the time I happened along, my parents were no longer spring chickens. According to a frequently cited family anecdote, I was supposedly the result of a drunken, day-bright May night in the West Fjords, maybe even the night of the First of May—for my father, one of the holiest days of the year. The late pregnancy was a huge shock for my parents, not least for Mom, who was terribly ashamed to be producing me at the age of forty-five. Dad was fifty.

When I finally arrived in the world, I turned out to be a redhead, which raised all sorts of questions. Dad’s hair was raven black. My grandmother, who lived with us, was convinced that the father of the baby just had to be our next-door neighbor …

My brothers and sisters were all much older than me, and in my childhood I had little or nothing to do with them. It was my parents, my two grandmothers, and my aunts and uncles who brought me up. My parents’ siblings were older than them, and every year an uncle or aunt died. Someone was always dying. Most of them got cancer and slowly wasted away, and at some point in the midst of all this death, both grandmothers died too.

I was considered to be difficult. Wild and impetuous, with a short attention span, I put up resistance to everything and everyone. I did, however, learn to talk extremely early and by the time I was just two I was chattering freely. I tended to hide myself away instead of playing with other children, but then again I was untamable, climbed trees and house roofs, ran out into the street, and put my safety at risk in all sorts of independent ways. I also liked throwing bad language around, the more indecent the better. I was a permanent provocation, and never predictable.

So right from the start I was seen as the black sheep of the family. I was a precocious child in a deadlocked world. My allegedly abnormal behavior was the normal reaction to abnormal circumstances. As is so often the case. The neighbors pretty much all thought there was something seriously wrong with me and doubted that I would ever cope in a normal school. After my umpteenth trip to the emergency room, they sent my mother and me to a child and adolescent psychiatrist, who, after thoroughly examining and evaluating me for over a year, diagnosed me as maladaptio. To many, it was just a fancy word for “retarded.”

By chance, there was in our district a school where a kind of pilot project was being tested out: lessons without the usual classes and awarding of grades. They worked on the so-called “open education” system, then a very revolutionary concept. In this school, I felt comfortable. In class, I behaved as conspicuously as possible, getting up to all sorts of mischief and raising a rumpus whenever I could. But that was okay. They took me as I was and treated me with respect, consideration, and patience. To begin with, I even performed exceptionally well with the curriculum. Reading in particular fascinated me, and soon I was reading everything I could lay my hands on, whether for children or adults, comics or non-fiction.

In reading, general knowledge, and telling stories I was one of the best, but when it came to writing and arithmetic, I was worse than mediocre. My letters were either upside down or back to front, my spelling was haphazard, and it was impossible for me to fit the words neatly on a line. The letters I wrote home on summer vacation were often passed around at family gatherings, where they were a reliable source of amusement. I was fifteen before I could really write.

I realized at a young age that I wasn’t cut out for everyday life at school. I still had the impression I was learning lots of useful things in the classroom because it helped me get a handle on everything I overheard on TV or read in books, but what the teachers taught us was rarely what really mat

tered. This insight grew with each passing year, and when I was eleven I just refused to go on learning school stuff. I’d had enough of the one-sided pedagogy and the soulless knowledge that school wanted to impose on me.

For example, I refused point-blank to learn Danish. I could see no practical use for this language. I would much rather have learned English, but unfortunately that wasn’t taught. Or why not Norwegian? I had a sister in Norway, I could visit her and at least make myself understood.

Mathematics was another subject I wasn’t all that good at. I knew that I’d never be brilliant at it, and I found it more reasonable to concentrate on what I was good at, rather than slogging my guts out to no purpose. Also, I’ve always been allergic to repetition. If I ever have to repeat the same thing over and over, I get so panicky and anxious that I can hardly breathe. That’s also why I’ve not appeared onstage as an actor much. After the endless rehearsals, the play hangs round my neck like an albatross and I can barely force myself to play the role on stage. Even for the premiere I have to make a real effort.

So I announced at home that I wasn’t doing any more schoolwork. Instead, I’d watch TV or read. This led to lengthy discussions between me, my mother, the teachers, and the headmaster.

“If you don’t learn anything, you’ll be a nobody. What are you going to be when you grow up? A garbage man, perhaps?” they said.

The idea was certainly tempting. Garbage men were the pirates of the modern era. They came at dawn, casually jumping onto the backs of their garbage trucks. They were free and independent. Whistling and cheerfully yelling out to one another, they swooped down on the trashcans and then, just as suddenly as they had appeared, vanished. For me, the garbage men were like heroes, and I looked up to them with admiration.

THE POLITICS OF MY YOUTH

My father was a political man through and through. Politics always played a central role in our home. When visitors came, the conversation was mainly about politics. When there was something about politics on the radio or television, the volume was immediately turned up. I tried to understand what was going on, but found such issues extremely boring.

In our home, the political world was divided into two parts: Left and Right. Mom didn’t have a great deal to do with politics. She voted for Sjálfstæðisflokkurinn, the Independence Party, the largest and oldest right-wing party in Iceland, but she refused to discuss it or to talk about politics at all. Dad, as I mentioned, was a Communist. He had been a member of the Communist Party of Iceland when it still existed, and his political orientation put its stamp on every aspect of our family life. Dad was a reliable, punctual, and efficient police officer in Reykjavík, but self-confessed Communists had very limited opportunities for advancement in the police force. That’s why he remained a mere traffic cop throughout his life, while his colleagues worked their ways up the career ladder step-by-step.

He thought highly of the Soviet Union, was a member of the Icelandic and Soviet Russian Cultural Association, and subscribed to a magazine called Soviet News. Whenever there were personnel changes in the Politburo of the Soviet Union, Dad was sent a framed photo of the new arrival to display at home. I remember how he passed on to Mom and me all of Brezhnev’s announcements. The only time of day we all met was the evening meal. When Brezhnev had said something worth noting, Dad took this opportunity to tell us about it. Neither Mom nor I were particularly gagging to find out what Brezhnev had said or done, but we kept quiet and nodded, looking interested.

Brezhnev was hanging on the wall in our pantry—on a photo, under glass. He looked grim, wore a kind of uniform, and was bedecked with all sorts of decorations and medals. In 1982, Yuri Andropov took over the office of Secretary General, and Dad got a photo of him too. Andropov did not look all that different from Brezhnev, except that he had fewer medals on his chest. Dad, proud and happy, wandered round the apartment with the photo and wanted to hang it up somewhere straightaway. But Mom wouldn’t hear of it. Dad continued to search for a suitable place, but Mom was adamant. Andropov wouldn’t have suited either our living room or the kitchen or the TV room, and so he ended up in the pantry next to his predecessor.

Mom and Dad subscribed to two daily newspapers: the right-wing Morgunblaðið and the left-liberal Þjóðviljinn. The pages of these newspapers accurately reflected the Cold War, as both of them commented on the day’s events from their particular perspective. The political leaders were either gods or the spawn of the Devil.

I myself subscribed to two magazines, Donald Duck and Youth, an Icelandic Christian magazine for children and teenagers, but both appeared only once a month. I studied each issue with great care, from beginning to end, hoping to come across something interesting. And if I already knew the current issue of Donald Duck by heart, I also grabbed the Soviet News—just to provide myself with reading material—which then kept me up to speed on those wonderful brand-new tractors that had been delivered to some Soviet farm.

Thanks to Dad, the newspapers, and the constant discussions broadcast on radio and television, I developed an aversion to politics. Politics was dumb, irritating, and boring. And unfair, too: just because the United States and the Soviet Union couldn’t agree, we all lived on a powder keg. The Soviets had their nuclear missiles aimed at America, and American missiles were aimed at the Soviet Union. It was only a matter of time before nuclear war broke out. In principle, it could happen at any moment. The consequences for the world would be devastating and would wipe out all human life on Earth forever. In my youthful innocence I often thought that the world would definitely be more peaceful and beautiful if people would just leave politics alone. If they’d just drop all the political drivel and talk about other issues, such as pirates, food, or garbage men.

PUNK

I was thirteen when I discovered punk. At that time it was quite difficult in Iceland to find out anything about punk. All we had was a single legal radio station that was limited to Icelandic choral and classical music. Often the pieces and their interpreters were not even identified, there was just a quick standard intro saying, “And now for a few cheerful bars from our record library.” Punk rarely, if ever, cropped up in the Icelandic media, and the music on offer was so limited that we mainly consumed it in the form of cassettes that we listened to over and over again. In the library there was Melody Maker—the weekly British music newspaper—and in the bookstores the German teen magazine Bravo.

I have no idea why Bravo was sold here, but I could always find articles about punk in it. Because I didn’t know any German, I had to rely on the pictures. Once I managed to get my hands on an issue with a poster of Nina Hagen, the German punk singer. I pinned the poster up on the wall of my room straightaway. Nina Hagen was my first great love: I had a hopeless crush on her. Until I heard her sing for the first time. What a disappointment! Either she mumbled in German, or suddenly started caterwauling an opera number. Punk and opera just didn’t go together, in my view. Also, I couldn’t understand her lyrics at all. The only thing I seemed to gather from listening was that she wanted to go to Africa. And what was punk about that? Were there even any punks in Africa? Wouldn’t she have done much better in England?

It was the Sex Pistols who brought me close to punk. This mainly had to do with the fact that Johnny Rotten was a redhead just like me. I wanted to resemble him in every way. This went so far that I for a time gave myself the stage name “Jónsi Rotten,” scribbled it in all my textbooks, and daubed the walls of houses with it.

Then I came across Crass, the British punk band that promoted anarchism, and everything else was overshadowed. What this band had to say was simply true, good, and right. This was the birth of my political convictions; they advocated direct action, animal rights, and environmentalism. From then on I collected all the material and information about anarchism I could get my hands on, often thanks to older friends.

In the following years I was a regular at the district library, where I made extended forays to track down everything that was related in an

y way to anarchism. Among other things, I dug out a few political science textbooks, in which there was shockingly little about anarchism. Nevertheless, I wrote out all the names that were mentioned in this context: Proudhon, Kropotkin, Bakunin, Malatesta, and all the rest of them. I recorded it all conscientiously. The specialized works on the topic were almost all in English and thus went over my head, as my language skills were only just sufficient enough to translate punk lyrics. Though Anarchism—Practice and Theory remained a closed book to me, at least I was able to locate an article here or there on Bakunin or Proudhon. The only book in Icelandic was a biography of Kropotkin, the author of The Conquest of Bread and a central anarchist thinker, a thick tome that I dragged home and plowed through from beginning to end. To my great disappointment, anarchism was barely even mentioned.

But I still had Crass. By this time I had also accumulated a remarkable archive of newspaper clippings, photocopies, and handwritten notes on which I kept what others had told me. One day I came across the magazine Black Flag, a British anarchist journal, which I used not only to improve my English, but also to establish contact by mail with anarchists abroad.

The more I learned about anarchism, the greater my certainty that I was an anarchist myself, and had always been one. Anarchy was and is for me the only way to a classless society, a mutually supportive society that respects the freedom of the individual and in which everyone can live his life freely and without external control, so long as he or she does not impinge on the freedom of others.

There was only one thing about anarchist ideology that I couldn’t subscribe to at all, and that was violence. As a child, I myself suffered from domestic violence for years, in the form of psychological abuse from my father, and I would never agree to inflict it on others. Violence was and is the dark side of human coexistence. Anarchy and peace, that’s what I longed for. This conviction led me to the teachings of Gandhi, and from Gandhi to Tolstoy and his Christian anarchy. Then followed a short detour through Max Stirner and his individualist anarchism, but in the long run I couldn’t identify with it. The Christian anarchists were ultimately only a detour as well, since so far, despite repeated sincere attempts, I haven’t managed to believe in a God.

Gnarr

Gnarr