Gnarr Read online

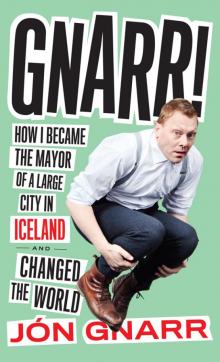

GNARR

Copyright © 2014 by Klett-Cotta—J.G. Cotta’sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger GmbH, Stuttgart

Translation copyright © 2014 by Andrew Brown

First Melville House Printing: June 2014

First published in German under the title

Hören Sie gut zu und wiederholen Sie!!!: Wie ich einmal

Bürgermeister wurde und die Welt veränderte by

Jón Gnarr, with the collaboration of

Jóhann Ævar Grímsson

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT

mhpbooks.com facebook.com/mhpbooks @melvillehouse

ISBN: 978-1-61219-414-1

eBook ISBN: 978-1-61219-414-1

A catalog record for this title is available from the Library of Congress.

v3.1

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

The Future

Iceland

Send in the Clown

The Politics of My Youth

Punk

Being Silly

The Financial Crash

The Third Way

What You Need to Be a Politician

Our Goals: A New Kind of Political Program

Democracy

The Campaign

The Best Party: We Are Better Than All the Others

Joke!

After the Election

Our Moral Code

Becoming Mayor

A Clown in City Hall

Wu Wei

My Family

Interview with Jóhanna (Jóga) Jóhannsdóttir

Facebook and Co.

Stress

Reykjavík—City of Peace

International Politics

A Letter to Barack Obama

NATO

The World Is Getting Better and Better

Repression

And Now?

The End

Inside Iceland

INTRODUCTION

Theories are clever things. In politics there are a lot of theories that make perfect sense: socialism, with its classless society, equality, and fraternity; or liberalism, which wants to give everyone enough leeway to work freely. Even in education and culture, there are smart ideas. And in the different religions. But unfortunately there is something to which no theory is immune: human weakness. Immaturity is one weakness. Selfishness another. Greed. No matter what ideology you hold to, sooner or later greed and selfishness get in the way, especially when it comes to human encounters.

In partnerships and families, at school or at work. Wherever people are trying to build something up, a single individual can bring everything crashing down. We know this from apartment buildings. You only need one person to step out of line and things get out of hand. In an apartment building, there are usually a few regulations about the use of laundry rooms and detergents. As long as everyone follows the rules, it all works beautifully. But there’s always someone who doesn’t seem able to do so. We’ve all met these people: the neighbors who leave their laundry hanging in the laundry room for days on end or use all of your detergent without asking. That’s the kind of thing that undermines the whole system. If we all try just a little bit to keep that from happening, I think we might not need any rules.

I’ve always divided people into two categories. There are the givers, the big-hearted people who assume responsibility and don’t leave any litter, in either the everyday or the more spiritual sense. And then there are the others, the people who don’t yield an inch because for some reason they can’t or won’t, perhaps because they think everyone else owes them something. They’re always quick to accept the help of others, but the idea of actually offering help themselves never seems to occur to them. These people are spiritual bloodsuckers.

I’ve been dragging this problem around with me my whole life, and I’m pretty used to dividing people into “givers” and “takers.” I feel good when I’m dealing with people who give me something, especially when it’s joy they give me. I’m particularly grateful for people who surprise me—those who have something beautiful, funny, or perplexing up their sleeves and conjure it up without expecting anything definite in return. And also those who simply give me a present—whereupon, I try to do the same.

In 2008, Iceland experienced the terrible consequences of the economic crisis. The country’s banks crashed in a catastrophic way, and we soon learned that the government had practiced no oversight of our banks whatsoever, with cronyism and incompetence at work at the highest legislative levels. The forces that brought about the economic collapse were selfishness and greed: the bankers made risky investments, enriched themselves, they bought big houses and fancy cars, and then all of the economic miracles of the Icelandic banking economy were exposed as fiction. The rest of the country suffered. Huge protests, directed at the government and the banks, soon followed.

As I detail in these pages, my response to the crisis was somewhat different: in 2009, I founded a political party with my friends: The Best Party.

In 2010, the party ran in the Reykjavík city council election. We won six of the fifteen seats, which meant that—after we formed a coalition government—I became mayor of Reykjavík, the capital of Iceland and the only big city in the country, home to most of Iceland’s citizens, as well as its government, banks, and thriving arts community.

When I entered politics I freely called myself an anarchist. But does that mean I seriously think that the dream of an ideal society in which everyone takes care of everyone else and everyone respects the rights of others can actually come true? A society in which you don’t need any rules, because everyone is so kind and mature and intelligent? No, I don’t think so.

When it came to democracy and politics, I had tended up until then to go for a comfy, rather passive attitude. The Best Party was my first attempt at getting involved. When I created the Best Party, I made a point of bringing in as many generous, intelligent, and sincere people as I could identify. Most of these people had, like so many others of the same ilk, ended up following the route of passivity in politics. With the Best Party I wanted to address precisely these people and get them to join in. I encouraged them to get involved in a positive way—even though the gibe that “the anarchist is one who criticizes society from the comfort of his armchair” also applies, unfortunately, to myself.

Leo Tolstoy once said, “Everyone wants to change the world, but no one wants to change himself.” But I feel that I have changed myself. I’ve done my homework. And next I want to try—just try, mind you!—to change the world. In a positive way. This essentially means leading by example. The Best Party wants to be a good example. We strive for honesty. We are against violence. And where others see problems, we provide solutions. All this is extremely tiring, but it’s what we’ve tried to do.

This book is an attempt to tell the story of my own political evolution and how I came to form the Best Party.

I’m often asked what I am particularly proud of in my party’s work. Of course, we’ve achieved a lot. Since my election as mayor of Reykjavík, we’ve created cycle paths, organized funding for social projects, redesigned urban areas, and supported new works of art for public spaces. But what I’m really proud of, to be honest, is just the fact that we still exist. I’m proud that a group of people from outside the political class has come together to try and change things, and has stuck with this ambitious project. We’re still here, and still with the original cast. We’ve also encouraged many young people to open their mouths and intervene wherever something strikes them as unjust, wrong, or pointless.

I can well imagine, at least I hope, that our actions and methods will provide a lesson.

THE FUTURE

A manifesto by Jón Gnarr, posted January 12, 2010, on the website of the Best Party.

Recently I was traveling abroad and suddenly felt the urge to pop into a swimming pool. I headed off to a kind of spa resort where I expected to find a pool, but—zilch. Instead, there were only a couple of hot tubs, and they weren’t even particularly hot. Still, there was a Jacuzzi bubbling away, so I gave it a try. Apart from me there was only one other bather present, an old man. I gave him a brief nod as I stepped into the water, then I closed my eyes and let the air bubbles rinse all the stress from my body. Suddenly the old man spoke to me.

“What do you think the future holds for Iceland?” he asked.

I was speechless. “I am from Iceland,” I finally replied. He didn’t reply and let his eyelids droop again. Did he know that I was an Icelander? And if so, how could he know? Only when we said goodbye in the parking lot did I notice that he had a special issue of the local paper—in which I had been profiled—in his sports bag.

The man was Knut Finkelstein, a futurologist from Frankfurt, Germany, who’d been fascinated by my interview in the paper and, like many other readers in Frankfurt at the time, apparently, was really worried about the future of Iceland.

On my foreign trips I often chat with children and teenagers. They too all seem to take a passionate interest in Iceland; many have read interviews and want to find out everything they can about the Best Party. I’m always very touched when I have a crowd of these young people around me, as they really seem to be deeply affected, blown away really, by all the things happening around them.

In Iceland, I recently visited a small village out in the country. There I met a tourist who told me proudly how he’d once eaten Icelandic lamb on a vacation through the United States. I was delighted to hear it, of course. Coincidentally, I had a big bottle of cocktail sauce in my bag, and I pressed it into his hand when we said goodbye. “Next time you have Icelandic lamb, dip it in this!”

Eventually the only cars around will be electric ones. And there’ll be batteries that last much longer than today. And Christmas tree ornaments that light up all by themselves. The people in power never think that far ahead. This is not good. They drift helplessly forward, bobbing along like someone clinging on to a weather balloon he’s lost control of. These are the people who call the shots in our country. When it comes to planning for the future, the authorities have failed to adopt a clear course that everyone can live with. Basically, they don’t give a damn about the future, as they think it’s completely irrelevant. So far, not a single member of Parliament in Iceland has had the courage to openly and honestly address the important questions about the future. No other party considers a programmatic look into the future as one of its values.

We do! We could certainly look forward to a rosy future—if people would only vote for us. If not, I’m afraid the outlook is dark. Everyone’s heart will sink down into his boots. Everything will be privatized, while the state nonetheless keeps it all under its thumb. Beer will be illegal again, just like being gay or driving a car. The EU will swallow us entirely and force us to give up everything we hold dear—such as fermented mutton testicles and smoked lamb. There’s no way to resist. If we put up a fight, Brussels will send troops to Iceland to shoot on sight anyone who violates EU rules. They’ll haul people out of their houses and shoot them down in the middle of the street—just because they’ve put too much salt on their food perhaps, or taken a pinch of snuff. Neoliberalism in all its pomp and splendor will make its triumphant entry, and sooner or later everything will be up for sale: we’ll have a society that lies somewhere between economic liberalism and the nanny state. Eventually, people will even sell off their own organs just to afford a bit of luxury. What can you really call your own when you have to sell a kidney in order to celebrate your birthday? Nothing. And everyone’s wearing the same clothes.

The other day I dreamed of the future. I was at a meeting with some high-ranking politicians. The main Icelandic ministers were there, but also Hitler, Mahatma Gandhi, and Chuck Norris, and these people were apparently now going to govern our country. What happened then I don’t know, except that all at once I had supernatural powers, as in The Matrix, and could walk through walls. In another dream I watched while, somewhere like the Austurvöllur in the city center of Reykjavík, children were being sacrificed to appease the shareholders. And all the old established politicians came to enjoy the children’s blood. The prime minister slurped so greedily that blood ran down from the corners of her mouth and seeped into her blouse, the finance minister was gnawing on a human bone, and Idi Amin had come to join them. The bystanders wept.

That’s a bleak scenario for the future. Do we want such a future for our children? Do we want them to be swallowed wholesale? The Best Party certainly doesn’t. We have an appointment with the future, and we’re going to meet it like a new friend, at first hesitantly and timidly, then more and more confidently and expectantly. In the society of the future, as we see it, everyone is happy and contented, uses free buses and swimming pools, and talks over all the reasons why the Best Party is so good. Disease, grief, and pain are things of the past. Nobody ever dies, they all live on, and if they need money, they just go into the nearest bank and have some printed—free of charge, of course. Anyway, money is now only of use as decoration or as a toy to play with. Because if we can turn our concept into reality, everything will be free. May we invite you to make a date with this rosy future? Then put your cross in the box marked Best Party.

ICELAND

Iceland appears on old maps as an island “beyond the habitable world.” Sailors warned you not to take a course to this Devil’s Island, because, on the old maps, the sea route to Iceland swarmed with sea monsters. When the ancient Greeks came this way, they quickly realized that there was nothing here, either for them or for anyone else.

People have tried to find a reason for the name “Iceland” for as long as anyone can remember. Some, for example, support the theory that the names “Greenland” and “Iceland” somehow got confused in hoary antiquity. Iceland is rather a green island. In no other country in the world do so many moss and lichen species grow as here, while in Greenland there’s not a single blade of grass to be seen far and wide.

But it is interesting that the prefix ice- in the Romance languages doesn’t have anything to do with the substance ice: it’s linked to island, being derived from the Latin word insula or isola. My own theory is that it might have come about this way: When the first Vikings set out on their raids into the northern seas, they must have come across a map belonging to Christian monks on which Iceland was indeed shown, but was simply named Insula. But the ancient Norsemen, who weren’t too great at foreign languages, couldn’t make heads or tails of this, and so did their own number on it; they changed the letters, added the ending “-and,” and lo and behold: it made sense. I don’t find this explanation all that far-fetched.

All Icelanders go swimming. It’s one of the undisputed advantages of this country that just about anywhere you go has a marvelously well-equipped swimming pool nearby. Icelandic pools are more than just swimming pools. They are complete spas with saunas, hot tubs, massage facilities, and solaria. The swimming pools are maintained by the local councils and seen as a basic service. Town councils are even obliged to allow their citizens reasonably priced access. If actual socialism has really found a niche anywhere in Iceland, it’s in the swimming pools.

In the pools, it’s just like in the phone book, everyone’s the same. In the hot tubs, which have always been very relaxed, bank directors and harbor workers sit together in the hot water and discuss politics and current events. Extra pools for the elite just don’t exist. The rich splash about in the same tank as the common folk. Outside, you look at people and you can see what social class they come from, you can read from their clothing and appearance how much they earn

. In an Icelandic hot tub you can forget all that. The stocky bald guy next to you might be a very rich ship owner with four lovers at once, and the sensitive young man opposite, who you’d spontaneously typecast as a philosopher or poet, could equally well be a shoemaker. Everyone pulls off their clothes and works up a nice lather in the shower in front of everyone else. This makes you more modest.

To understand Iceland, you have to go to the pool. It’s the swimming pools that forge us into a nation, more than anything else I think.

Despite what you may have heard, our solidarity with the Norwegians, Danes, and Swedes has its limits. We don’t feel particularly close to the mainland Scandinavians, although the first settlers in Iceland came from precisely these countries. Instead, we feel in some mysterious way attracted to the Finns. Icelanders often like to emphasize how “Icelandic” the Finns are, and the Finns willingly return the compliment: they find us pretty “Finnish”—just as relaxed, awkward, and depressed. This secret bond between Finns and Icelanders must have something to do with the Finnish sauna culture. You see, the Finns are, just like us, a naked people. In Finland, it’s the most natural thing in the world to wander around stark naked in front of strangers, without feeling ashamed of your body or the bodies of others.

In Icelandic swimming pools you can regularly see foreign visitors who find this unabashed nakedness strange. The tourists wrap themselves up tightly in their towels before coyly discarding their underwear and getting into their swimsuits. These inhibitions always amuse us Icelanders—while we, with our towels thrown casually over our shoulders, let our freshly showered breasts or dicks cheerfully dangle as we stroll around.

As long as I can remember, in Iceland it was all pretty straightforward. Here, strictly speaking, nothing happens. The country has just 320,000 people, so if someone falls off his bike, it’s worth at least a headline in the daily paper. If celebrities from abroad come to visit, they often emphasize how enjoyable and relaxing life is with us—in contrast to the grotesque media circus that springs up around them everywhere else. There are no tabloids and no paparazzi.

Gnarr

Gnarr